Examining the premise of a leaky pipeline

Original research

This podcast features original research by Kyle McEntee, LST's Co-Founder, and Deborah Merritt, John Deaver Drinko/Baker & Hostetler Chair in Law, Moritz College of Law at The Ohio State University.

Many observers worry about a leaky pipeline for women attorneys once they leave law school and enter practice. The leaks in the pipeline, however, start much earlier—during the law school admissions process. By analyzing data collected by the ABA and LSAC, we have identified three early leaks that affect the representation of women in the legal profession. Addressing these leaks would improve gender diversity in law schools and the legal profession. It might also help schools draw talented new applicants to their J.D. programs.

Leaks

- Women obtain 57.1% of all college degrees, but they account for just 50.8% of law school applicants.

- Women who apply to law school are less likely than men to be admitted.

- When women are admitted to law school, they attend schools with significantly worse placement rates (and U.S. News rank) than men.

These Problems Visualized

Enrollment of women as a percentage of total enrollment reached an initial high in 2001, just as the incoming 1L class reached 49.4% women. The percentage of women students declined in subsequent years, falling to 46.7% in 2007. In 2016, women finally hit the elusive 50%.

The application gap

Despite women obtaining 57.1% of all college degrees and pursuing graduate degrees at higher rates than men, women accounted for just 50.8% of law school applicants in 2015. Women have made up the majority of college graduates since 1982.

The admissions gap

Men have received at least one offer of admission at a persistently higher rate than women since at least 2000, the most recent year for which data are available. The gap exceeded three percentage points in all but two years.

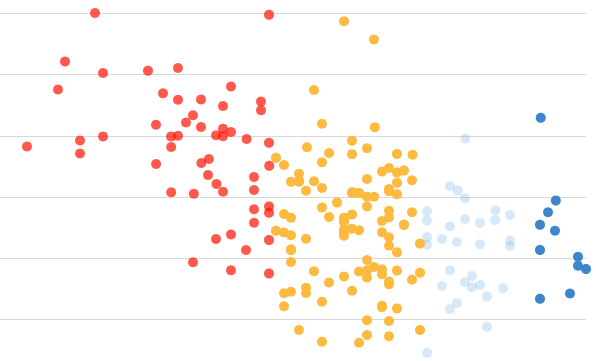

The prestige gap

LT, FT BPR: 68%

% Women Enrolled: 48.7%

Fast facts

- In fall 2015, women made up 49.4% of all JD students at ABA-accredited law schools. Those women, however, were not evenly distributed among schools.

- The best and worst schools mirror each other. At the top 50 schools for long-term, full-time (LTFT) jobs that require bar passage, 53.4% were men. At the bottom 50 schools, 45.5% were men. The top 50 schools average an employment rate of 77%. The bottom 50 schools average 38%.

- To put this another way, the correlation between the percentage of women enrolled at a law school and the percentage of that school's graduates obtaining LTFT legal jobs was -.520 (p < .001).

- Thus, while women occupy almost half of all law school seats, they are significantly less likely than men to attend the schools that send a high percentage of graduates into the profession. Even if graduates of the latter schools ultimately enter the profession, they start at a disadvantage.

The prestige gap is growing

There was a similar relationship between a school's job outcomes and gender composition in 2011, when the ABA began collecting detailed employment data. The gap then, however, wasn't as large as it is now. In 2011, the 50 schools with the best employment records enrolled 55.1% men. The 50 schools with the worst records enrolled 50.3% men. That was a worrisome gap of 4.7 percentage points—but not nearly as large as the 7.9 percentage point spread that exists today.

LT, FT BPR: 51.4%

% Women Enrolled: 37.3%

We lack detailed employment data for years before 2011. So to explore this trend further, we turned to the U.S. News rankings. In 2001, when women's law school enrollment first approached 50%, there was no significant relationship between a school's gender composition and its rank in US News. In 2006, there was a small correlation between the two (.137) that approached statistical significance (p = .066). It seems, therefore, that the prestige gap for women law students emerged since the turn of the century. There are traces of the gap in 2006, it becomes evident by 2011, and it is stark by 2015.

What's causing the clustering?

Unlikely explanations

- Preference for non-law jobs. The leak does not seem to occur because women law graduates prefer non-practice jobs. NALP data show that the percentage of women graduates obtaining jobs that require bar admission is almost identical to the percentage of men graduates obtaining those jobs—although the women, graduating from schools with less successful placement records, may have to struggle harder to secure those jobs.

- Regional differences. Nor does this leak seem to be due to bias in limited regions of the country. We divided schools into the nine geographical regions used by NALP (and the U.S. Census) and found that the bias existed in every region. The correlations were not statistically significant in some regions, due to the small number of schools, but they consistently pointed in the same direction: In 2015, women held fewer seats at schools with high rank and/or strong employment outcomes.

- Difference in major legal markets. When we separated schools into those located in major legal markets and those in other areas, we found the same phenomenon: the bias existed (and was statistically significant) in both groups of schools.

These findings suggest that the gender bias is very unlikely to stem from regional differences among schools or women's geographical choices. No matter how we divide schools geographically, we find the same gender bias in every group of schools.

Plausible explanations

- U.S. News ,ania. Schools, especially those in the top half of the U.S. News ranking, reportedly stress LSAT scores over other admissions factors as they fight for better rankings. Declining applications may have pushed schools to focus even more narrowly on LSAT scores as a way to maintain or increase their rank. This would disadvantage women, who have lower LSAT scores on average than men. The timing of the bias we identified—especially the sharp increase after 2011—fits with this hypothesis.

- Higher cost of attendance. Schools award an increasing number of scholarships based on LSAT scores. Men, with higher LSAT scores on average than women, may receive scholarships to more prestigious schools.

- Women Don't Ask. Women may not negotiate as aggressively as men for scholarships. Even if schools attempt to make equal "first offers" to men and women, men may negotiate for higher scholarships that allow them to attend more prestigious schools.

A way forward

Fixing the leaks in the law school pipeline would benefit women, schools, and clients of the legal profession. None of these groups can afford to lose talented women from the profession. We plan to examine the leaks further by gathering additional data from law schools, the American Bar Association, Law School Admissions Council, and National Association for Law Placement.

There are several steps that stakeholders could take now to explore and improve the status of women in law school admissions.

- The Law School Admissions Council could provide additional data to us and other researchers, allowing fuller examination of gender pathways through the admissions process. The data should include information about race/ethnicity as well as gender, because the intersection of multiple social identities can cause sharp differences in treatment.

- The American Bar Association's Section on Legal Education should resume publishing the gender breakdown of entering classes for each law school. If the ABA does not currently collect gender-specific information about scholarships, it should do so and share that information publicly through its Standard 509 website. Once again, the data should account for race/ethnicity along with gender.

- The National Association for Law Placement should encourage and help schools to examine gender differences in student placement. NALP already provides detailed gender data to schools. In particular, schools could examine the relationship between LSAT (and other admissions criteria) and job outcomes. Those analyses could inform both admission/scholarship decisions and placement efforts. NALP itself could expand its traditional of analyses highlighting differences based on gender and race.

- Editors at U.S. News should reexamine the weight that LSAT scores receive (especially compared to undergraduate GPA) in rankings. The weight given to LSAT scores may be driving gender inequity.

- Individual Law Schools should examine their own data to identify gaps in the treatment of men and women. To explore these questions fully, schools should include race/ethnicity and—when available—socioeconomic background in their analyses.

- Are women admitted in the same percentages that they apply? If not, what factors produce the discrepancy? Is the difference due to LSAT scores or to other credentials?

- Do men and women receive similar scholarship offers? If not, what creates the differences?

- Is the scholarship negotiation process similar for men and women? Schools can track these processes by looking at the timing of offers, contact records with applicants, and changes in offers. Admissions offices likely track these matters to manage their own scholarship budgets; examining the data through a gender lens could yield key insights.

- Schools should consider providing data about admissions and scholarship offers to independent researchers who will treat the data confidentially (using human research protocols) to identify general trends.

- Law Schools should work with Pre-Professional Advisors to explore why female college graduates are less likely than male ones to apply to law school. Does the problem lie in law schools' reputation? In the substance of their programs? In the cost? In the nature of jobs available after law school? Once again, researchers should be sensitive to differences across race/ethnicity, socioeconomic class, and type of college attended. Researchers should also be sensitive to the persistent gap over the last several decades, i.e. this gap is not new to the transparency era. Successfully addressing the gender gap in applications could yield significant benefits to law schools suffering from smaller applicant pools.

- Law Schools should work with the Practicing Bar to identify issues that discourage women from pursuing careers in law. Work/life balance is a significant issue for many women—as well as for a growing number of men. The recession and contractions in the legal industry appear to have exacerbated these problems. What steps can we take to restore the profession's attractions to both men and women? As above, other factors (race/ethnicity, socioeconomic background, family status, age, and income) will influence answers to these questions. There is no single "woman" and no one answer to increasing the profession's appeal to women.

Columns

- Above the Law: A Woman Lawyer's Hard Lesson: You Can't Have It All by Elizabeth Berenguer, Law Professor at Campbell University School of Law

- Bloomberg Big Law Business: Diversity's Death by a Million Little Paper Cuts by Julia Shapiro, CEO of Hire An Esquire

- Lawyerist: Women In The Law Podcast: "The Leaky Pipeline #1"

- Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly: Examining the Leaky Pipeline by Karen Hester, Executive Director at the Center for Legal Inclusiveness

- Hire an Esquire: Are Women Set Up To Fail? by Mary Redzic, Product Marketing Manager at MerusCase

- The Girl's Guide to Law School: The Leaky Pipeline: LSAT and Law School Applications by Susan Smith

Podcast guests

- Deborah Rhode

- Kim Amrine

- Deborah Merritt

- Kyle McEntee

- Jay Shively

Transcript

Kimber Russell: I'm Kimber Russell. This is LST's mini-series about women in the law, where we discuss sexism, intersectional challenges for lawyers from under-represented groups, and more. For the next two weeks we'll discuss the leaky pipeline. In next week's episode, we discuss retention and success. This week, we take a careful look at the leaky pipeline metaphor, as well as whether conventional wisdom holds true about gender balance at U.S. law schools.

The leaky pipeline metaphor has been used in a variety of contexts: science, engineering, business. But it always gets to the same idea: some demographic does not succeed like we expect.

Historically our profession has not been inviting to women. And after entering the legal profession, they frequently exit prematurely. As a result, fewer women emerge as successful practitioners and leaders.

Deborah Rhode is a law professor at Stanford Law School and the director of the school's Center On The Legal Profession. When she started at Stanford in 1979, she was the second woman on a faculty of 36 men.

Deborah Rhode: The problems I was interested in three decades ago are still with us, albeit in a less pronounced form. Part of the problem is the lack of consensus that there is a significant problem. So many leaders of the profession believe that opportunities are more or less equal, and that if women haven't reached the top, it's because they lack commitment and capabilities for those positions.

Kimber Russell: There's significant empirical research showing that women are underrepresented at the highest rungs of the profession.

Deborah Rhode: Women are still 18% of the equity partner in large law firms, less than a quarter of general counsel. They're also under-represented among tendered law professors and over-represented among assistant professors. And for women of color, the attrition rates, especially in the large law firms, are edging close to 80 and sometimes 90%.

Kimber Russell: Deborah put a book out this fall called Women and Leadership. It focuses on women's underrepresentation in leadership roles, and asks why it persists and what we can do about it.

Deborah Rhode: It points out that the three main barriers that people identify still are unconscious bias and stereotypes, in group favoritism – sort of the old boy network and exclusion from informal structures of support in career development -- and, finally, work-life issues.

Kimber Russell: While not insurmountable, these barriers stand between women and success in the legal profession. According to Deborah, the conventional explanation is that it's simply a matter of time before the pipeline fills.

Deborah Rhode: “Barriers have come down, women are coming up, and full equality is just around the corner. Just give it a chance to work.†When I was a much younger scholar I thought there was more truth to that than I do now. The assumption back in those days was let's just let the older generation die off and people who've grown up with more egalitarian attitudes are going to implement them in the workplace. But what we've seen is that problems are more structural, they're more unconscious, they're more systematic, and more intractable than once we assumed.

Kimber Russell: For all of the problems that the leaky pipeline speaks to, it is still an imperfect metaphor. First, 100% retention is unrealistic and not even desirable for society: interests and values evolve over time. And that's okay. To stick with the metaphor, we don't need to ensure no leakage, just address discrepancies in retention by various demographics, including gender. Second, a pipeline implies an end. Even women who make partner or become judges experience limiting forces. Addressing the pipeline only gets us part way to a fairer and more effective profession.

Deborah Rhode: It assumes that everybody wants the same thing, which is access to the positions of power, prestige, and financial reward as they're currently structured. And there's a lot of evidence that many people don't and an increasing number of men don't either. Structural changes have to be made in the way that work is allocated. The expectations regarding face-time and 24/7 availability, they're just not workable for people who want a life in addition to their professional career.

Kimber Russell: When we acknowledge the leaky pipeline, in part we're saying that the legal profession does not set women up to succeed. But as Deborah Rhode implied, defining success is key. There's no single trajectory — no single definition of success.

For some people it's earning a job title: federal judge, partner, district attorney. For others it's helping the less fortunate, making loads of money, or changing law and policy. For many it's striking their preferred balance of professional and non-professional activities and responsibilities. And these measures of success aren't exclusive.

But whatever your definition of success, chances are gender plays some role in how easy or difficult it is to achieve — man or woman.

Kim Amrine is a partner at Frost Brown Todd in Cincinnati, Ohio. She's the director of diversity at her firm. Kim pointed out another flaw in the common pipeline analogy.

Kim Amrine: Sometimes you are looking at an exact moment in time where the leak occurs, and it's the gush right of the women that are departing at that exact phase. But I don't think that analogy or that visualization is reality. There's no secret time at which or secret point at which the pipeline is broken and you need to reinforce it with tape. I think that unconscious bias is what makes the components of what the pipe is comprised of to not be as strong. So you will continue to lose women along the way and maybe you push them a little farther through at a faster pace, but if your pipe is not made of as strong of a material — if it's not made of double thickness copper — then you are going to lose the contents of what you are trying to carry through that pipe.

Kimber Russell: In other words, unconscious or implicit bias limits all varieties of success in law. Kim highlighted these disadvantages by way of an analogy presented by Arin Reeves, a leading researcher on leadership and inclusion.

Kim Amrine: We all begin the race, it's the same race, we're all trying to get from point A to B. It's not that half of us don't want to finish the race or don't want to win the race. But imagine if we all start the race with the wrong shoes. And then you say ready set go. And if we look at the end and we're amazed that everyone is not finishing at the same time and the same place, it's amazing what you can do if you have the right size shoe. And likewise it's amazing, looking at the beginning of the pipeline to the end of the pipeline, if you've truly eliminated unconscious bias, then you are really starting and finishing the same race with the same equipment and the same shoes.

Kimber Russell: Coming up, we look at gender imbalance in law schools. But first here's a word from one of our show's producers, Olympia Duhart.

Olympia Duhart: Among other projects, Law School Transparency helps prospective law students decide whether and where to go to law school. If you're a student trying to make this important choice, or know someone who is, send them to LST Reports dot com. No resource can compare.

Kimber Russell: The challenges posed by implicit bias loom large, but over the last several decades, women in the workforce have made great strides, paving the way for future generations of women. One accomplishment in the legal space is the dramatic improvement of the percentage of women in law school.

In 1965, just 1 in 25 law students was a woman. That number steadily climbed to 1 in 4 in 1975; 1 in 3 in 1980; and since 2000, the proportions have been roughly equal -- though always slightly more men than women.

But a closer examination of the data exposes leaks earlier in the pipeline.

Kyle McEntee is this show's executive producer. He's also a co-founder of Law School Transparency. Kyle and Debby Merritt, a law professor at The Ohio State University, analyzed a heap of data and made several startling discoveries. During this segment we'll hear from both of them. Here's Debby.

Debby Merritt: There really are 3 very significant leaks in the pipeline that occur right out the gate of law schools. The first of these leaks involve women applying to law school. Even though women are 57% of those college graduates, they account for only about 51% of the law school applicants.

Kimber Russell: If women applied at the same rate as men to law school, applications would increase an astounding 16 percent.

So what are some possible explanations for why women shy away from law school?

Debby Merritt: THey make up an even greater percentage of the pool of masters degrees than they do for college degrees. And women even outpace men in obtaining PHDs. So it's not because they don't want to continue their education or they don't have money, and it's not because they have the wrong majors. Women in fact far outnumber men in the humanity, social science, and inter-disciplinary majors, which is the pool that feeds law schools.

So there's something about law school or the legal profession that women don't like that make the profession or the education less appealing to them.

Kimber Russell: Earlier this episode, Stanford Law Professor Deborah Rhode and law firm partner Kim Amrine both described what makes the profession less hospitable to women. Next week's episode dives much deeper into why that is. But that's beyond the scope of this week's show. Based on available data, it looks like potential applicants are perceiving that the profession is not a great fit, and are choosing to pursue other careers.

The second leak comes during admissions.

Debby Merritt: Women who apply to law school are less likely than men to be admitted. For the class entering in 2015, law schools admitted about 80 percent of the men who applied but just 76 percent of the women who applied -- that's a 4 point difference, which is fairly significant. And that type of gap has existed for many years, it existed even when law school admissions were quite competitive.

Kimber Russell: And what are some possible explanations? Here's Kyle.

Kyle McEntee: So it could be a difference in LSAT scores. On average women do score 2 points worse on the test and the distribution curve is actually shifted to the left, which means there are fewer higher scores. And although women have higher graduate GPA's on average, most law schools weight LSATs more heavily than GPA when making their admission decisions.

Now, of course, admissions is not strictly a numbers game. So I do wonder if schools view men and women's extracurricular activities in the same light. Implicit bias affects a wide range of decisions in our society and schools really need to ask why they are less likely to admit women.

Kimber Russell: That leaves us with the third leak, which is also the most dramatic.

Kyle McEntee: Even when women are admitted they attend lower status schools than men, and these schools offer significantly worse job outcomes and reputations. Now given how obsessed our profession is with prestige, this not only affects women practicing law, but it probably affects the ease of success once in practice.

Debby Merritt: In other words that 50/50 gender split we see nationally is masking a very different reality. Kyle and I looked at this more closely by building a database that included the job outcomes that law schools provide for their graduates, the gender composition of their classes, the U.S. news ranking of the schools, and several other factors.

Kimber Russell: The important starting point is that women made up 49.4% of all J.D. students at ABA-approved law schools in 2015. Not half, but not far off. It's a one percentage point difference between men and women enrolled.

Debby Merritt: There are 11 schools in the country that place at least 85% of their graduates in jobs that require bar admission. Just 46.6 percent of their students are women. That's a 7 point spread between the percentage of women and the percentage of men enrolled at those schools.

At the next rung down there are schools that place between 70 and 84% of their graduates in jobs that require a law license. In those schools the percentage of women is even lower than in the top group. Just 45.7% of the students enrolled at those schools are women.

Kimber Russell: That's almost a nine point spread. The next rung down includes schools that place 50 to 69% of their graduates in jobs that require a law license. Kyle and Debby found that just 47.6% of the students were women. That's a spread of about 5 percentage points favoring men.

Kyle McEntee: So given that the national picture is just about 50/50 this means that women are actually clustered at the schools that place less than half of their graduates in those gold standard law jobs. At these schools 53.9% of these are women which is almost an 8 point spread. The big question, then, is: are these differences statistically significant?

Debby Merritt: The odds of this distribution happening by chance are less than one in a thousand. And that's just not a small statistical quirk. On a practical level these differences are huge. Another way we can look at the relationship between the percentage of women at a school and the school's employments outcomes is to compute what's known as the correlation between that two. In 2015 that correlation was -.52. That means that the better the job outcomes at the school, the less likely that women were to make up a large percentage of the class. And the size of the negative correlation is what social scientist would call a large correlation. We don't normally see in human behavior that large of a correlation between two different variables.

Kyle McEntee: In sum, women college graduates are less likely than men to apply to law school. Law schools admit a smaller percentage of women applicants than men. And most important, women law students are not spread evenly across law schools. Instead they cluster disproportionately in schools with the weakest in employment outcomes. And as it turns out the last one is actually a new and worsening problem.

Debby Merritt: In 2011 there was a correlation between the percentage of women enrolled in a school and the degree of the school's employment success, but it was much smaller. It was just -.34. That's what social scientist would call a moderate correlation instead of a large one.

Kimber Russell: Prior to 2011, law schools were not transparent, so Debby used a different yard stick to see if these patterns were around at the start of the century. While neither Kyle nor Debby like the U.S. News rankings, schools, students, and employers do accept these rankings as a measure of a school's prestige.

In 2001, when schools had just gotten to 50/50 nationwide, women were evenly distributed amongst schools with different ranks. But by 2006 the story had started to change. Although the pattern was not yet statistically significant, it had started to emerge.

Debby Merritt: By 2015 the pattern was statistically significant and quite stark. Today the top 50 schools are the mirror opposite of the bottom 50 schools.

It's perverse because most educators would say that women have more opportunities to succeed today than they did 15 years ago, but in fact they are less likely to be attending the prestigious schools and the ones that have excellent employment outcome than men are. If women aren't attending those schools and then getting the jobs that those schools are able to place their graduates in, then we not going to diversify the legal profession.

Kimber Russell: So what on earth is going on at law schools? One possibility is that the applicant pool has changed since 2001. Here's our executive producer Kyle McEntee again.

Kyle McEntee: So I don't think that's what's going on. In 2015 there were actually more women than men applying to law school. There have been some ebbs and flows in percentages since 2000, but the national profile is fairly consistent.

Kimber Russell: We talked to an admissions dean at a well-regarded law school about the pressure admissions professionals feel to meet institutional enrollment goals.

Jay Shively: My name is Jay Shively. I'm Dean for Admissions and Financial Aid at Wake Forest University School of Law.

Kimber Russell: Jay has a ton of experience. He started his career in admissions in 1999, but took a break between 2004 and 2009 to work for the Law School Admissions Council. During his time there, the admissions world underwent a transformation.

Jay Shively: Just prior to going to LSAC, I was Dean for Admissions at the University of North Carolina's Law School. And I just remember it being such more of a qualitative process. Like I met with so many more people, we talked about their goals and aspirations. Talked about whether UNC was a good fit for them. Certainly numbers were part of the equation, but in one year in particular, just anecdotally, I remember clearly that we dropped 8 or 10 points in US News and I spent the whole weekend sort of preparing a report for my dean about why that happened and what we were doing to address those problems. And I went to talk to my dean and he was sort of like eh, these things go up, they go down you know. We can't worry about that too much.

Kimber Russell: It's harder to imagine that happening these days.

Jay Shively: When I got back, after 5 years, when I started back at Penn State, and I don't think it is a function of the school, I've seen it across many of my colleagues across the country. I think that it is very much a process where it is so numbers driven, that I work much more in spreadsheets now. And certainly I still meet with students and we talk about the values of the Wake Forest experience and the Wake Forest legal education, but my choices are limited as an admissions professional so much more now by making sure that I meet these particular goals. It's just a totally different process than I feel like it was.

Kimber Russell: This is a natural result of law schools recognizing what students value.

Jay Shively: Schools have begun to appreciate and understand the impact that U.S. News has on candidates' view of the admission process, and their view of the quality of the law school and legal education in general. Time after time after time, student surveys tell us that U.S. News, location, and scholarship are the three factors on which they are making a choice about where to go to law school.

So it just makes sense now as schools become more savvy in the way that they market themselves and the way that they present themselves to the world, U.S. News has to be a part of that equation.

Schools have gotten really analytical in sort of understanding the methodology, understanding the impact, trying to figure out the areas where they can have an impact on U.S. News. That often means employment numbers, bar passage, and admission numbers. Those are the things where they can have the most impact.

Kimber Russell: So here's one possible explanation for the unequal representation of women at the best law schools. Maybe, in their quest to secure or improve their U.S. News ranking, law schools have decided to emphasize LSAT scores more. And since women do worse on average than men on the LSAT, the schools lose sight of gender balance as they jockey for their position.

Jay Shively: It could be “catastrophic†for a school if they lost a couple of points on U.S. News.

Some schools I think have the benefit of not having to be in that game, but if you're a top 50 school, I think you have to be very aware of your medians and how losing a point or gaining a point might impact your ranking and thus the sort of the students that might be attracted to you.

Kimber Russell: Coming up, Kyle and Debby discuss where they think the data may take them as they continue to explore their surprising findings. First here's a few more words from Olympia Duhart about a new nonprofit that's tackling the leaky pipeline for racial minorities.

Olympia Duhart: Pipeline to Practice enhances diversity in the legal profession by supporting and nurturing diverse law students and early-career attorneys at key stages of their academic and professional development. Visit PipelineToPractice dot Org to learn more.

Kyle McEntee: Debby I know neither of us are really quite satisfied with the research at this point. We see something important here but we don't quite understand what's going on and we want to explore it more. So what are some of the other places that you think we need to explore as we continue this research?

Debby Merritt: The first place I'd like to look is at the way in which law schools make offers for financial aid. We know how important financial aid is to students these days. There is a list price for law school but relatively few people pay that price at most law schools, and the extent of the discount really makes a difference in terms of a student's desire to go to law school or ability to go to a law school.

Kyle McEntee: And of course rolled into this discussion about financial aid is that those offers at law schools do concentrate largely on LSAT score. And so it could be related to our main thesis that [02:50] it's the focus on the US news rankings causing this effect to strengthen over time.

Debby Merritt: We also know that prospective students negotiate with admission officers about what their scholarship aid will be. And I wonder based on research in other areas whether women are as aggressive in that negotiation as men are. And if they are not as aggressive then they not getting the best scholarships from the top law schools, and they may be forced to settle for a law school that gives them a good upfront scholarship offer but is not one that has as much prestige.

Kyle McEntee: So do you think there is any chance that over the last 15 years we have seen the women prospective student cohort change their desire for more prestigious laws schools?

Debby Merritt: I wouldn't think so. I think there was a time, when I first went into teaching now more than 30 years ago, where women were more likely to stay in the city where they were located. They were with their families so they didn't want to leave a particular location and they sometimes would trade off location for prestige.

Kyle McEntee: So it'll come as no surprise that we both really want to figure out how to better understandn this problem at a number of levels and that the first step to it is to be gathering data from Law schools. What are some of the data points you think that we should focus on in asking law schools to share with us? We need to look at what percentage of applicants at individual schools were actually women. And then what were their LSATs and GPAs to figure out if there actually was some kind of implicit bias or if there was some sort of revealed preference.

Debby Merritt: We would also like to look at I think at the timing of offer, timing of scholarships offers, amount of the first offer, the number of negotiating contacts between the law school and the prospective student, what the ultimate scholarship offer was [26:50] and then off course whether the student matriculated, if not what other school did they go to.

Kyle McEntee: This is information that, if schools and LSAC do not have right now, they could collect and study. There may be some reluctance on the part of law schools to disclose that information, not because they are worried that we would find huge gender disparity that they don't want us to know about, but because law schools consider this information to be a trade secret — they use it to compete in the marketplace with other law schools.

That said, there's a great case to be made to allow us to analyze these data anonymously.

Debby Merritt: They really have two interests here. One is that I think that most people in legal education are committed to the prospect of increasing diversity of the profession. They want the legal profession to be opened to both men and women. So if we could make a case that these data will help us figure out why women don't have the same footing that men have, I think that law schools will be open to that.

The second is that law schools really are worried about where their applicants are going to come from. There's been a crash in law school applicants and it's really not recovering yet. If we can show the schools that there's a pool of women out there who have not applied to law school, who perhaps are not being admitted on the same basis as men, and perhaps are not attending the higher ranks schools in the same numbers as men, we might be able to help them figure out how they can attract more talented students in addition to diversifying the profession. And that's a pretty important promise to make to law schools these days.

Kimber Russell: Thanks for tuning in. There's no roundtable this week, but next week we talk more about the leaky pipeline and what employers and employees can do to make the profession more inviting to women. I'm Kimber Russell. This episode was produced by Kyle McEntee. Music by Brad Kemp. Thank you to all of our guests and to Olympia Duhart, Marissa Olsson, Ashley Milne-Tyte, Carin Ulrich Stacey, and Susan Poser for your help. We also want to thank Alli Gerkman and Diversity Lab for a generous donation very early in the project.

Women In The Law is a production of Law School Transparency. To learn more about LST, visit lawschooltransparency.com. To learn more about this mini-series, visit LSTRadio.com/women.

Explore episodes

Hey Sweetie!

Sexism in the legal workplace

In the Media

How women lawyers are portrayed on TV and in the news

Leaky Pipeline #1

Examining the premise of a leaky pipeline

Leaky Pipeline #2

From hiring to retention to leadership

Multiple Identities

Intersectional challenges in the legal profession

Solutions

Rules, sanctions, and awareness

Search

Listen on

Distribution partners

In addition to traditional podcast channels, the series will enjoy wide distribution through a growing number of partners. Each partner will publish at least one article per theme. Across a wide variety of networks we will foster a lively discussion over the show's eight-week run.

We hope to empower both women and men to recognize and constructively address a wide range of workplace issues that negatively impact women, the organizations and firms they work for, the clients they represent, and the society we all live in.

Documents

Media coverage

- New York Times, November 30, 2016

- Time, November 30, 2016

- Bloomberg Big Law Business, November 30, 2016

- St. Louis Business Journal, November 30, 2016

- Inside Higher Ed, November 30, 2016

- ABA Journal, November 30, 2016

- National Jurist, November 30, 2016

- Australasian Lawyer, December 1, 2016

- Global Legal Post, December 2, 2016